Free: "The First And Last Spaghetti Bowl" (Football, Not Food)

NOTE: When A paid article reaches the third month, it becomes accessible for you. The below was dated on November 9, 2023. However, I put it today (January 1) - the traditional day for the major bowls.

“Did your 85th man tell you about this game?” Howard Gorrell asked the children of the 85th Infantry Division soldiers in the Facebook group called “85th Infantry Division Custer.”

In December 1944, a war photographer named Margaret Bourke White received a telegram from the Life Magazine headquarters and burst into laughing after reading it. It assigned her to take pictures of the Spaghetti Bowl on January 1, 1945. This mentioned bowl was the football bowl game, not a food bowl.

“No, Dad did not tell me, although he was a football buff,” answered Howard Gorrell, the son of Interim Captain Paul E. Gorrell of Company D of the 337th Regiment.

Toward the end of 1944, the U.S. Army decided to give its troops aboard a taste of a back-home tradition—football on New Year’s Day - January 1, 1945. To entertain the soldiers and airmen, they arranged the Spaghetti Bowl in Florence, Italy, the Riviera Bowl in Marseille, France, the Coffee Bowl in London, England, and the Potato Bowl in Belfast, North Ireland.

“Same here; my dad never mentioned it. Surprising since he was an athlete. I'm guessing he was in some dugout in the snow, staring at Germans staring at him,” replied William Sarokin, the son of Private Seymour "Stony" Sarokin of Company D of the 337th Regiment

The Spaghetti Bowl organizers selected Florence's Stadio Giovanni Berta (now known as the Stadio Artemio Franchi). The Air Force assigned the pilot crew of a P-38 aircraft to patrol overhead in case the German Luftwaffe dropped by to blast the stadium.

“My dad never mentioned it,” responded Don Jones, the son of Staff Sergeant Roy E. Jones of Company C of the 337th Regiment.

The United Service Organizations (U.S.O.), Women's Army Corps (W.A.C.), and military nurses scrambled the plans to entertain the halftime show.

Brooklyn Dodgers manager Leo Durocher and New York Giants outfielder Joe Medwick agreed to come to the Game to speak at halftime.

“Dad never said anything about it either,” responded Charles A. Trebes, Jr., the son of Private First Class Charles A. Trebes, Sr. of Company I of the 337th Regiment

The Army Krautclouters selected Lou Bush, a former University of Massachusetts Minutemen star. At the same time, the 12th Air Force Bridgebusters tapped Major George "Sparky" Miller, an assistant coach with Indiana University, to coach.

Army’s Sergeant Cecil Sturgeon was the lone player in the Game with National Football League experience, so he served as the Army's captain. Lieutenant George Barnes, a former quarterback at the University of Maryland, captained the Air Force.

The team rosters are posted in the Link List at the bottom below.

“Negative,” returned Mike Freeman, the son of First Lieutenant John Freeman of Company K of the 337th Regiment.

On the Game Day, some troops jumped onto trucks and jeeps and rode three hours in from the front that morning. The Red Cross learned that the weather forecast would be cold and provided concessions like hot dogs, coffee, and donuts.

The attendance was estimated at 25,000. After the Game, the fans had to return to their camps instead of spending overnight in Florence.

One reporter mentioned that the Army mascot was a mule. He must be a city boy since this mascot was actually a scrawny burro. (One 10th Mountain Division veteran told me that the Army had treated mules much better than its soldiers.)

More stories about the bowl game and more photos by Margaret Bourke-White are posted in the Link List at the bottom below.

“My Uncle Joe didn’t mention it. I read about it in ‘Fifth Army History,’“ “wrote Sean Hockens, the nephew of Second Lieutenant Joe Davison of Battery A of the 910th Field Artillery Battalion.

Here is an excerpt from the ‘Fifth Army History” book.’

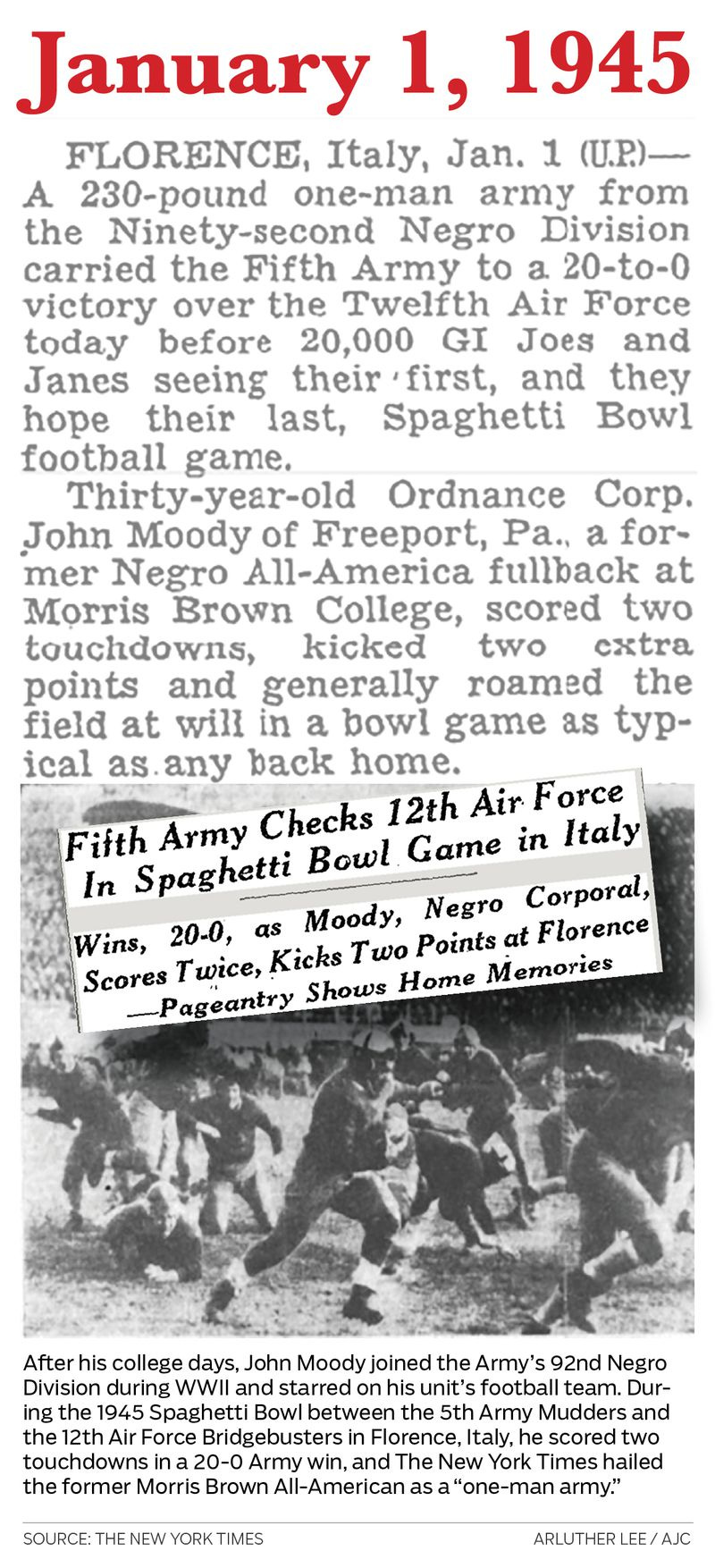

“The climax of the holiday attractions was the "Spaghetti Bowl" football game between opposing teams representing Fifth Army and Twelfth Air Force played on New Year's day in the cement municipal stadium in Florence before approximately 25,000 service men and women, many of whom were trucked to the game from the front line. Players on the victorious army team were drawn primarily from combat units, and all the traditional sidelights of a big game in the United States were reproduced.”

"No,” wrote Gary Haskins Jr., the son of Private First Class Gary Haskins Sr. of Company D of the 337th Regiment.

Being a former end of the University of Kansas football team, Second Lieutenant Robert “Bob” Dole of Company I of the 85th Regiment of the 10th Mountain Division.

listened to some regular bowl games on the radio in Hampton Roads, Virginia, before preparing for Italy on January 4, 1945, to support the 85th Division in Italy. On the following day, he read the below news.

[Note: Morris Brown College running back John “Big Train” Moody (1939-41) was among the seven inductees of the Black College Football Hall of Fame Class of 2022]

Other Bowls Results:

Riviera Bowl: Railway Shop Battalion Unit defeated Army All-Stars, 37-0, at 18,000 spectators.

Coffee Bowl: Army Air Base Bonecrushers won over Army Airway Rams, 6-0. 1,200 spectators.

Potato Bowl: Army tied Navy, 0-0, with an unknown number of spectators.

And the Nazis were a no-show.

Howie’s Questions:

“No. I learned about it when I bought this booklet program on eBay,” replied Steve Cole, the son of Staff Sergeant Newton F. Cole Jr. of Battery B of the 328th Field Artillery Battalion.

On January 1, 1945, Soldiers Paul Gorrell, Seymour Sarokin, Charles Trebes, Roy Jones, Gary Haskins, and John Freeman were in an assembly area north of Lucca (60 miles/92 km west of the stadium) to assist the all-black 92nd Division (known as Buffalo Division) in patrolling the line. Newton F. Cole Jr.’s battery was in Camaiore, Italy (65 miles/105 km from the game site.) Raymond Holt’s tank and Joe Davison’s Field Artillery could be in this Lucca area.

How did the Army football team recruit John Moody, who happened to be Corporal of the 92nd Division? Did the Army excuse him from patrolling for playing football?

Why did the Army not recruit Private Seymour "Stony" Sarokin, a super athlete from New York City, to play? [After the war, he played for the Chicago Cubs minor league teams.]

“My dad (752 Tank) never knew about it. He was still on the line, and his diary entry for January 1, 1945, says he spent from midnight to 6 AM on January 1, 1945 firing harassing missions. My guess is that a lot of rear-echelon Army and Air Corps guys enjoyed the Game,” replied Bob Holt, the son of Sergeant Raymond Holt of Company B of the 752nd Tank Battalion.

Were the soldiers mentioned above aware of the “top secret” announcement about the bowl game? Or Bob Holt might be right about most spectators not being needed to combat the enemy directly.

Did Lieutenant General Lucian Truscott, the new commander of the Fifth Army, attend this Game?

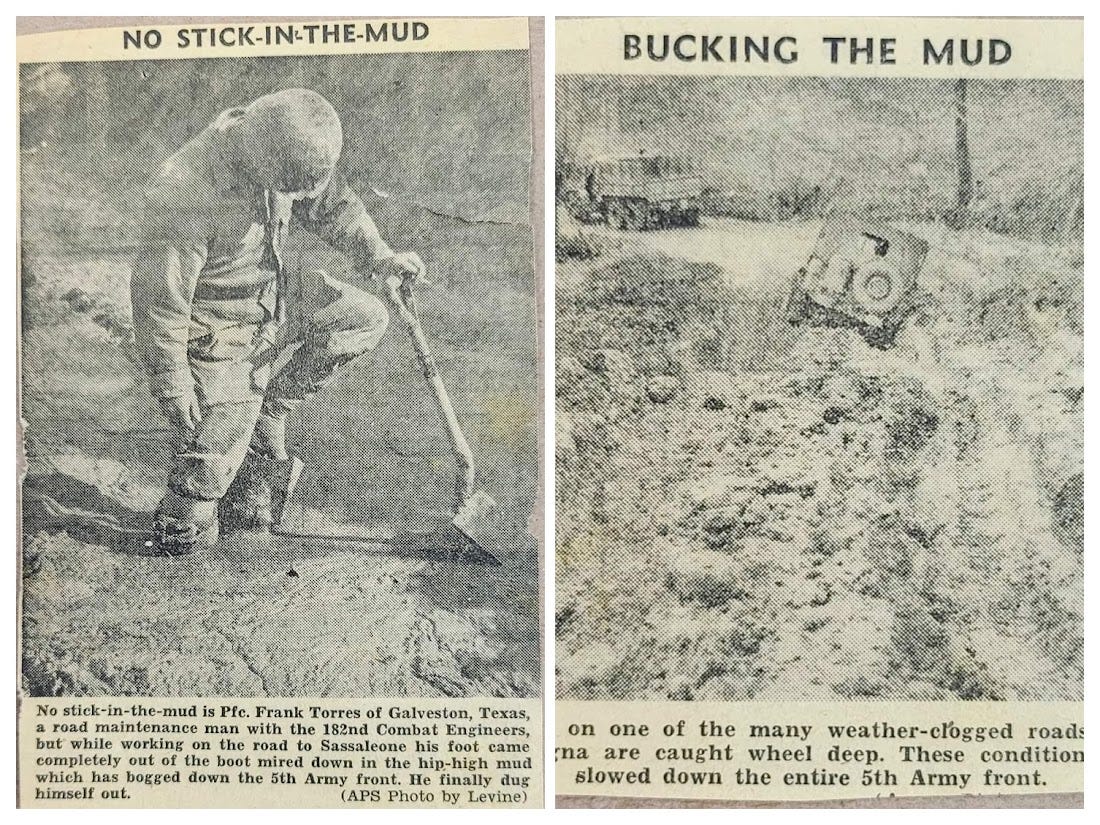

Why did they call them “Army Mudders”? The below pictures can quickly tell you why.

LINK LIST

New Year’s Football in Wartime Italy: The Story of the Spaghetti Bowl (Life Magazine)

A Rare Game Spaghetti Bowl Played In Italy for WW II GIs (The Oklahoman)

Margaret Bourke-White (Wikipedia)

Spaghetti Bowl (American football) (Wikipedia)

Spaghetti Bowl (National Pasta Association)

Private Seymour "Stony" Sarokin (Custermen.com)

Spaghetti Bowl Game Program (Use a magnifying glass to read players’ names)